Why No One Agrees About Vibe Coding

It's either the future or a scam, depending on who you ask

Everyone has opinions about “vibe coding”, and those opinions differ widely. Depending on who you talk to, vibe coding is either the future of the technology industry or doomed to fail.

Part of the problem is that “vibe coding” is a broad term for something that has much more specific use cases. AI code generation (aka “AI codegen” or “codegen”) is a better term, as you can use AI to generate code in a variety of ways, in a variety of contexts for a variety of purposes. Thinking about it this way, it’s clear why there is no agreement.

Interestingly, none of those radically different opinions is incorrect. They just refer to different forms of codegen, like different facets of a complex shape. In some cases they are doomed to fail, and others are the future of the technology industry.

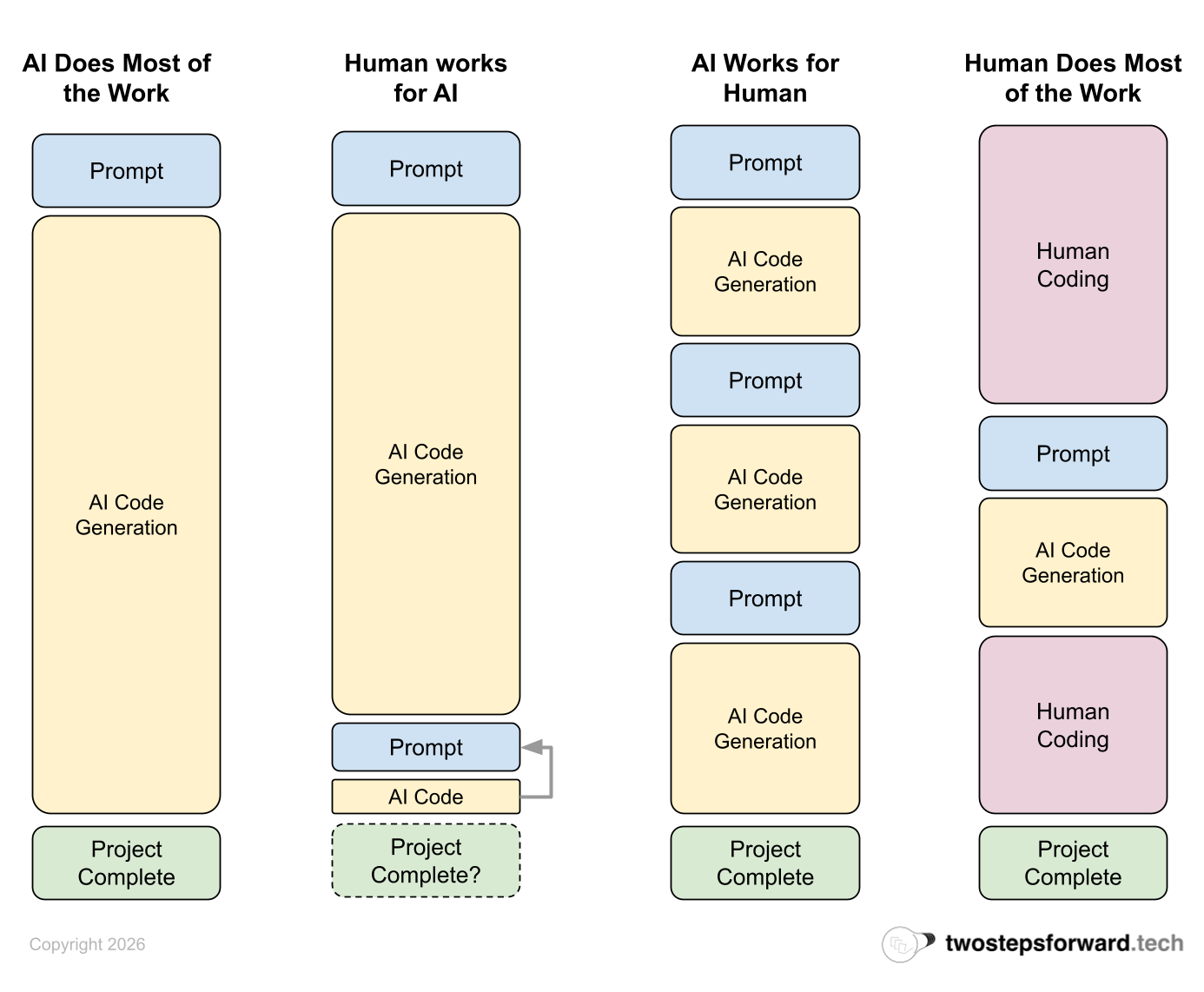

We can group these forms into a few categories:

The AI does all the work

The Human works for AI

The AI works for the Human

The Human does all the work

We’ll break down each category to show how it differs, and why popular opinions might be wrong about them.

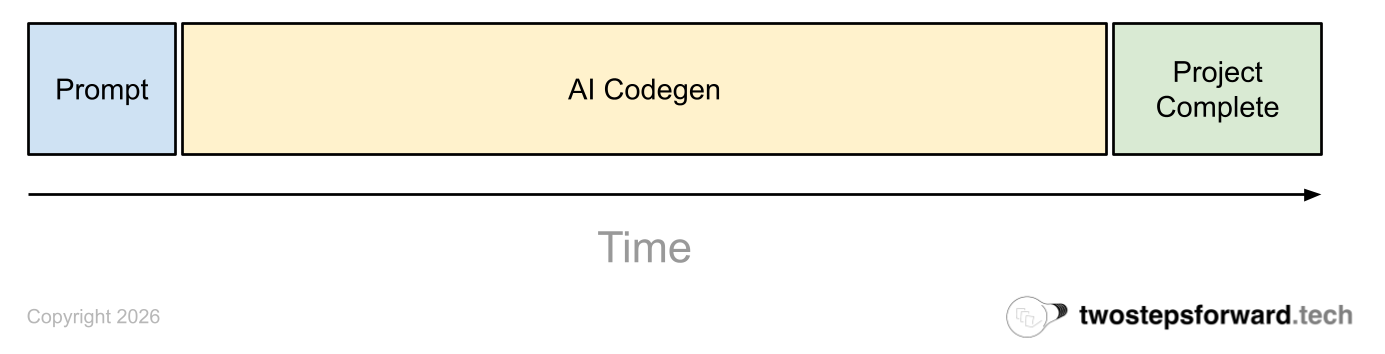

Form 1: The AI Does All The Work

This first form is the one that is most romanticized: a human writes a prompt and the AI generates all of the code to fulfill the request on the first try (aka “one-shot”). It has the appeal of our dream of AI, where it can do all of the work for us without requiring oversight or assistance.

Today it is possible for codegen systems to perfectly complete a request in one-shot if a few things are true:

The problem is simple

The request is specific

The human is flexible on the end result

However, those three things are rarely true at the same time. Either the problem is complex, the request is vague or the human has a specific result they want. When any of the three doesn’t hold true, the result of the codegen doesn’t meet the expectations and is considered a failure.

This is where most of the doom-saying about vibe coding originates. For non-technical users it might be impossible to know if the problem is hard or how to make a specific request. As a result, they try and it fails and the entire category is dismissed.

On the other hand, more sophisticated users use this form as a strawman to dismiss the entire category. It’s easy to create examples of failures when you attempt to one-shot a complex problem with specifics that can’t be captured in a single prompt.

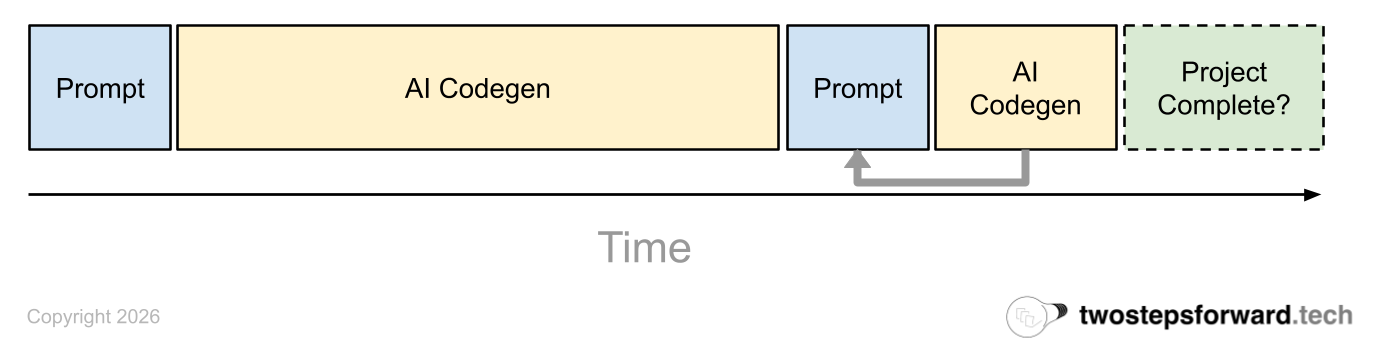

Form 2: The Human Works for the AI

This form is much more common, and is typical of the experience of non-technical folks using platforms like Loveable. The initial prompt gets 80% of the way to the desired result, but there is a lot of time and iteration to try and get the last 20%. Many times the end result is never achieved.

Most of the frustration with AI comes from people using this form. The first 80% comes so easily, and is done so well, that it seems like the task should be easily completed. Unfortunately, the last 20% is usually the complexity and if the user does not have the skills to guide the AI to the solution it can get lost in loops and dead ends.

As AI improves, this is getting better. In the earliest days of Lovable or Cursor, it was common to have the AI get lost in a loop in the last 20% while tackling hard problems. Today, that’s rare.

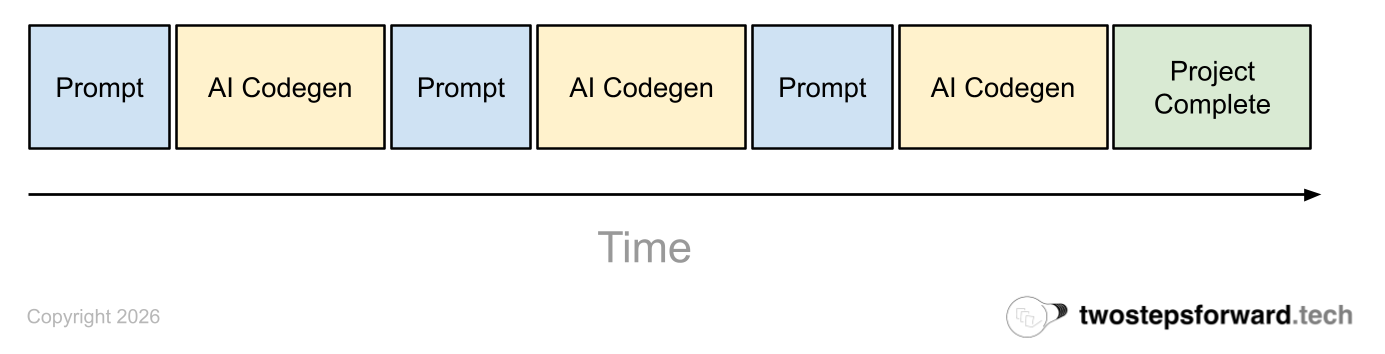

Form 3: The AI Works For the Human

Experienced software engineers use codegen very differently, as they know what they need to build and how. The AI becomes the channel by which the human creates the software in the form they need it, following the design they desire.

This looks like a conversation between the human and the AI, where the human gives the AI specific tasks in a specific order that add up to the end result.

For example, the first step might be to update the SQL database model. The next step is to update the REST API and the final step is to update the React web app to consume the new API. By breaking down the problem into discrete tasks with clear inputs and outputs, the AI produces an expected result that can then be modified and improved through further discussion.

This is the model that Cursor is ideal for, unsurprisingly, and which Claude Code excels. While one-shot of a complex problem might be impossible, this approach works extremely well on even complex problems. Especially with large, complex codebases where changes might have unintended side effects (and all of the code does not fit into the context window) this approach is necessary.

The people who talk about AI as the future of development are often referring to this model as well. As an experienced developer, once you get good at this you realize that all software will be written this way in the future. It’s fast, efficient and predictable.

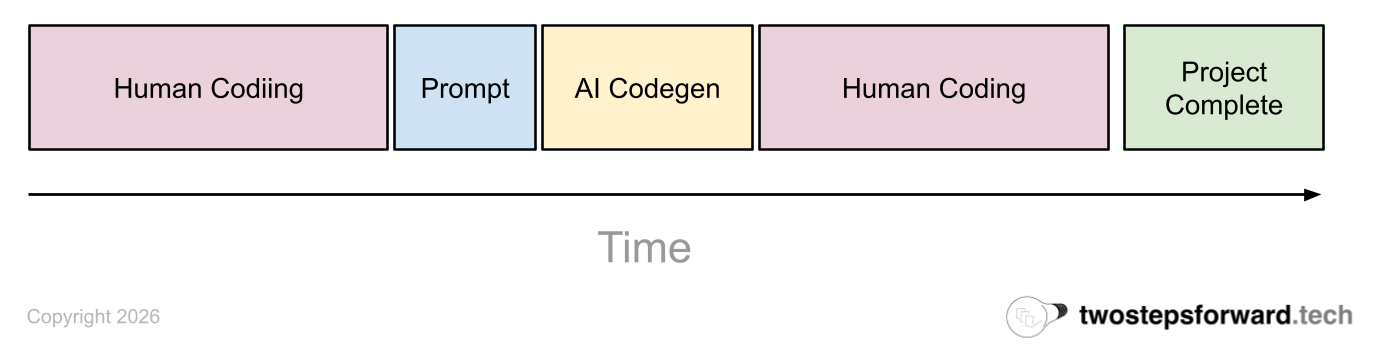

Form 4: The Human Does All the Work

The final form is more typical of people who are resisting the move to AI. In these cases the human still writes most of the code themselves, and relies on the AI as an advisor on questions of syntax or design. AI becomes an interactive version of StackOverflow, filling in gaps in the developer’s knowledge.

This is where AI codegen started. In the earliest versions of Cursor, it was simply an IDE with a chat box on the side you used to get advice from AI. The fact that there are still hold-outs using this reflects more on how hard it is to adapt to massive changes in process for people with a lot of experience.

Of all the forms, this is the one that will definitely disappear. The productivity of developers who use AI interactively is too high, and this process too slow, to compete.

The Bottom Line

When you look at vibe coding this way, it’s clear why there is so much disagreement. Non-technical users want one-shot completion of complex projects, and engineers have found a very different way of using AI that delivers better results in professional development.

The good news is that this is not the realm of opinions. As AI gets better, one-shot development (Form 1) will get more common and the frustration of Form 2 will fade away. Developers will all converge on Form 3 and Form 4 will go the way of punchcards for programming.

In a decade, it will be hard to remember how software was developed before AI.